In strategic Domain-Driven Design (DDD), we distinguish several key elements. One of them is Context Mapping. Bounded Contexts can and even must communicate with each other. This is an integral part of software system design. Today, we will explore the types of mappings and describe them with real-world examples.

Embedding in DDD

When it comes to DDD, we divide it into two components. Strategic DDD deals with high-level decisions, defining contexts, ubiquitous language, and communication between components (bounded contexts). Tactical DDD, on the other hand, breaks down the elements located within the bounded contexts into their constituent parts. This is a significant simplification, but for the purposes of this blog post, we can assume that this is sufficient information to understand the context of Context Mapping within this overall framework.

Sources

The literature that is helpful on this topic includes primarily the so-called “blue book” by Eric Evans and “DDD Distilled” written by Vaughn Vernon. As a supplement, we can use the DDD Crew repository.

I could end the article by simply linking to these sources. However, I want to expand on the definitions with examples from real-world business. This is precisely the most difficult part of educating oneself and others about DDD. Few companies share their practices, and we mostly rely on theoretical examples proposed by educators. Today, we will try to break this pattern and discuss Context Mapping in a more practical way.

Open / Host Service

This situation involves one Bounded Context opening its API and allowing dependent services/modules to use it based on the API documentation (usually), exposing the language of its context externally but not reacting to the specific requirements of its clients. This is the most common model, especially in microservice applications, where Bounded Contexts communicate with each other via REST API.

A real-world example could be the Spotify application or another streaming platform. Let’s assume that one Bounded Context is the Catalog, and the other is the Player. In this situation, the Catalog exposes its API or Facade (if it’s a monolith). This is a typical scenario where the Player can use the data provided by the Catalog in any way it sees fit on its side, but only through the public API contract. This is particularly useful when we want a part of our system to be publicly accessible.

Conformist

In this type of mapping, we are dealing with an upstream->downstream relationship. It closely links the conformist part of the system (BC) with the upstream. It can be said that decisions made by the upstream can disrupt everything in the downstream BC that is based on the contract with the upstream. The downstream does not have its own domain model in this area and directly adopts the upstream model, accepting the risk of its changes.

A real-world example could be any application that uses Amazon’s API. Amazon makes changes to its API? It breaks backward compatibility? You have to adapt. In this case, clear and predictable behavior from the API provider is essential to keep up with changes in the upstream system.

However, this involves communication with an external module. To better illustrate this with an example of a provider within our organization, let’s consider any product company. Let the upstream be BC User Management, owned by the central platform team. The model should contain basic entities: User, Role, Permission, and the Value Object Status. Let’s also assume that the team responsible for this BC has a strong position in the company, or its Tech Lead is a close collaborator of the management.

In this example, let’s use a Bounded Context called Billing as the downstream service. Billing needs information about users as a client; it doesn’t own the user identity and doesn’t have the budget or mandate to create its own model (for example, due to staffing shortages).

In practice, this will mean that the Billing module will import DTOs from User Management and use them directly. In this case, fields such as user_id, role, or status (or many others) will be stored in exactly the same form. There is no mapping or translation involved.

If, one day, BC User Management changes statuses by name, alters the semantics of roles, or removes a field from the model, the Billing model will, in common parlance, “break down.” Importantly, this is acceptable in this type of mapping. This is usually because the cost of isolation would be greater than the cost of adaptation. It also indicates that the Billing team has less influence on the company’s overall strategy.

ACL (Anti-Corruption Layer)

An ACL (Anti-Corruption Layer) acts as an intermediary layer between two Bounded Contexts. Its purpose is to protect the downstream model from being contaminated by the language used in the upstream context and to provide resilience against changes, although this resilience is still limited.

Compared to the Conformist model described above, the main differences, besides the larger investment required during downstream BC implementation, are:

- Downstream does not accept the upstream model

- Downstream has its own domain-specific language

- Integration is achieved through translation, not direct use of the models

A real-world example is a system that handles subscription billing and uses a payment gateway or payment systems such as Stripe. The typical data structure in such systems includes: Customer, Invoice, PaymentIntent, and Subscription. The API changes relatively frequently, and the terminology is also subject to significant variations.

Our Bounded Context, which we’ll call Billing, might use completely different terminology, for example: Payer, Charge, BillingPeriod, Settlement. In this case, the Billing team doesn’t want the semantics and naming conventions to leak into their model (because if we change payment providers, we might have a problem, and the change would leak into our model).

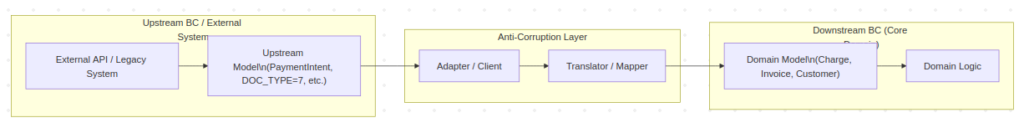

We then create an ACL, which is a layer that maps data from the payment system. The class using the API could then be called, for example, BillingPaymentAdapter, and we add a PaymentMapper to it, which acts as our ACL. For clarity, I’ll include a diagram:

As we can see above, our downstream model is completely independent of Stripe or any other provider. Here’s a good example of the implementation: the ACL (Anti Corruption Layer) should reside in the infrastructure layer if we are using a Hexagonal architecture or its equivalent in other approaches. According to good practices (SOLID principles), dependencies should only flow in one direction (the domain should not be aware that the ACL translates from an external system). For example, creating a dependency like domain -> infrastructure or domain -> Stripe SDK is not allowed. The domain in our code should only contain information about the ACL class interface (for example, PaymentProviderPort).

Shared Kernel

In some situations, we want the common parts of Bounded Contexts and their model to be deliberately separated, limited, and shared by both modules. The key characteristics are that the code in the shared kernel should be kept to a minimum, and it requires coordination on both sides of the relationship (there is no upstream-downstream relationship, but rather a more balanced one).

This mapping makes sense when both Bounded Contexts truly share the same concept and definitions, the cost of duplication and synchronization is greater than the cost of sharing, and the teams on both sides are aware that changes must be coordinated collaboratively.

As an example, consider a business application containing the following modules: Identity and Audit. The Identity module is responsible for users, roles, permissions, and access policies – typical functionality in many B2B platforms. The Audit module will maintain a log of events, recording who performed a given action and when, as well as fulfilling any legal requirements such as ISO or SOC2.

In both contexts, UserId and TenantId will be common concepts. This means that validation rules, semantics, and Value Objects will be shared – for example, a Value Object named Permission. In the shared-kernel (if it’s a modular monolith), we can place the following classes:

shared-kernel/

identity/

TenantId

UserId

security/

Permission

time/

Clock In the code above, we see that the common parts of both models will be controlled by both teams. Any change to TenantId must undergo review from both sides, and contract tests must be written to ensure compatibility from both sides of the relationship.

Shared Kernel is recommended in cases where the organization has a high level of organizational maturity, including shared code reviews, shared testing, and a clear division of responsibilities. Furthermore, the teams must collaborate closely, share common business goals, and be able to agree on changes to the Shared Kernel. Imagine a Money class. If changes are made to it, they will likely affect the entire organization globally, thus the sensitivity to change is balanced across all teams.

However, care must be taken not to overload the Shared Kernel with too many things. It should have limited responsibility, reduced to a minimum, and the issues it covers should be marginal to the Bounded Contexts that use it. Ideally, the Shared Kernel should be small, slow-changing, and contain Value Objects rather than complex processes or entities. It’s also good if it doesn’t have dependencies on infrastructure – this significantly simplifies design and coding. When a divergence in definitions is more dangerous than coupling, we use a Shared Kernel. In other cases, other types of mappings should be considered.

Published Language

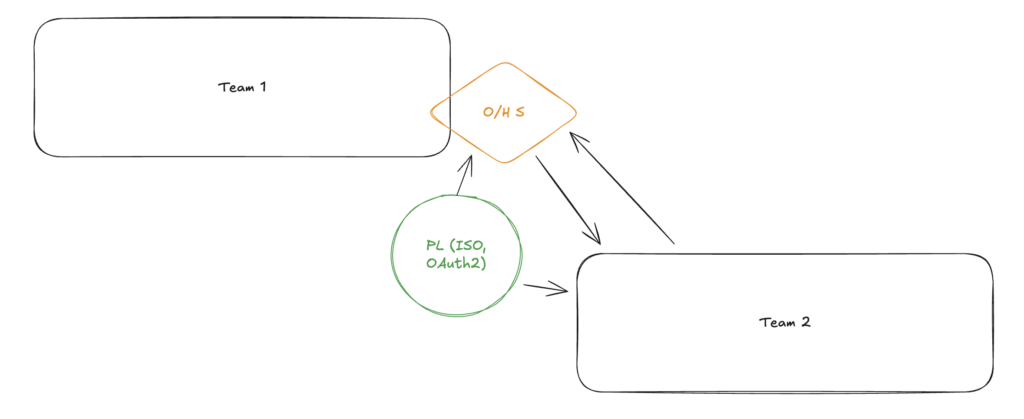

It must be admitted that this form of mapping has sometimes much in common with Open/Host Service. I’m referring primarily to the form of collaboration between teams. One team opens up a space with documentation, which other Bounded Contexts access to obtain information about naming conventions, interaction documentation, and some details about the processes the API provides. Let’s look at great example of the difference.

OHS without PL: The bank provides an API for transfers. The /transfers endpoint accepts JSON with the fields sender_account_id, recipient_account_id, amount_in_cents, and currency_code. This is OHS – the API is open and documented. But if, in 6 months, the bank changes amount_in_cents to amount_minor_units, all clients will have to adapt. Each downstream system translates this data into its own domain language.

OHS + PL: The same bank, but it implements the ISO 20022 standard for payments. It uses precisely defined types such as CreditorAccount, InstructedAmount, and PaymentIdentification from the XML/JSON schema defined by an international committee. Now the semantics are common and stable. When Visa, Mastercard, and SWIFT use the same ISO 20022, everyone speaks the same language. A change would require ratification of a new version of the standard by the committee.

To summarize the diffs:

Open Host Service operates at the integration architecture level (HOW we expose services: REST, gRPC, access policy), while Published Language operates at the domain semantics level (WHAT the data means: vocabulary standardisation, contract governance). These are not “patterns used in combination,” but orthogonal dimensions – you can have an open API with your own dialect (OHS without PL) or a closed ISO 20022 standard only for partners (PL without OHS).

Let’s look at the visualisation:

The concept is therefore very simple. Let’s take, for example, applications that use OAuth2 for authenticating/authorizing their users. When you log in to an application using your Google account, the OAuth Published Language is at work:

access_token– access tokenrefresh_token– refresh tokenscope– scope of permissions

This language is published as a standard, and everyone understands it the same way – whether it’s Facebook, Google, or GitHub. Therefore, with an open API, we can connect directly to the services mentioned above thanks to this language, which is published as a universally known standard.

Separate Ways

This mapping format assumes that integration between components (BC) is not needed or, in some cases, will even be impossible. In this scenario, for the purposes of a given context, we can freely duplicate the ubiquitous language, write our own solutions, processes, and algorithms because another team has no insight into or interest in seeing the changes and assumptions that our project implements.

Sometimes it’s easier to write your own package/module than to integrate with an internal or external business component. An example of this would be an ERP system for a manufacturing company.

Context 1: Production Planning

- Manages the production schedule

- Assigns machines and operators

- It tracks the progress of production orders

- It has its own definition of “Order” = a production order with dates and machines.

Context 2: Quality Control

- It has its own definition of “Order” = a batch of products to be inspected

- It conducts product inspections

- It records defects and non-conformities.

- It generates quality reports.

In this case, the order is something completely different, and production planning is not closely linked to Quality Control. The reasons for this separation can vary: for example, the current solution “works, so we don’t touch it,” different teams, different legacy systems: Production Planning uses an old SAP module from 2005, while Quality Control has its own system purchased from a different vendor in 2018, different data models, or different work rhythms of the Bounded Contexts.

Let’s assume the cost of writing the integration is 200,000 PLN. Let’s say this represents 7 months of work for one programmer working on a B2B contract – based on average senior developer salaries – I encourage you to read my previous article discussing the situation in the Polish IT market.

The question to ask in these types of problems is: is it worth integrating two services if the only benefit is some nice diagrams from the architects at the end of the day? Of course, this is an oversimplification, but in this particular case, there’s no point in integrating something that naturally operates completely independently in the business. I hope this illustrates the use cases somewhat.

Big ball of mud (rather antipattern)

Oh, I could write for hours about this. In my 10-year career, this is the type of mapping I’ve encountered most often. The results of modeling Bounded Contexts in this way are usually mediocre, if not downright terrible. It leads to mixed aggregates, excessive coupling, a large amount of knowledge hidden in the developers’ heads, and difficulties in obtaining testable code.

This is actually just a simplified overview. It’s important to remember that most business or B2B applications will have subsystems built in this way. Very often, the code within these subsystems will be crucial to the application’s functionality. To solve the problem encountered with this mapping, it’s necessary to break down the large “ball of mud” into smaller, more understandable Bounded Contexts whenever possible. Sometimes, the only way is to create new Bounded Contexts for new features and separate them from the “Big Ball of Mud” using the ACL (Anti-Corruption Layer) discussed above.

I think I’ll discuss the topic of the “Big Ball of Mud” in another article dedicated to legacy systems and ways to modernize them. So I invite you to follow the blog; many interesting stories based on real-world examples (anonymized, of course) from my previous projects may appear here.

Not all topics were covered

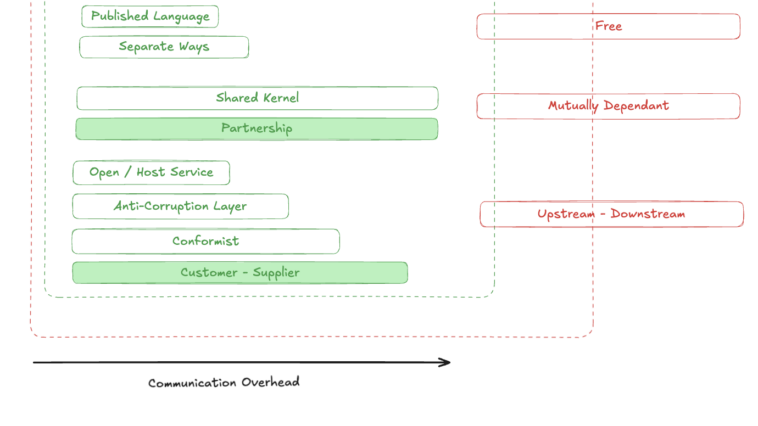

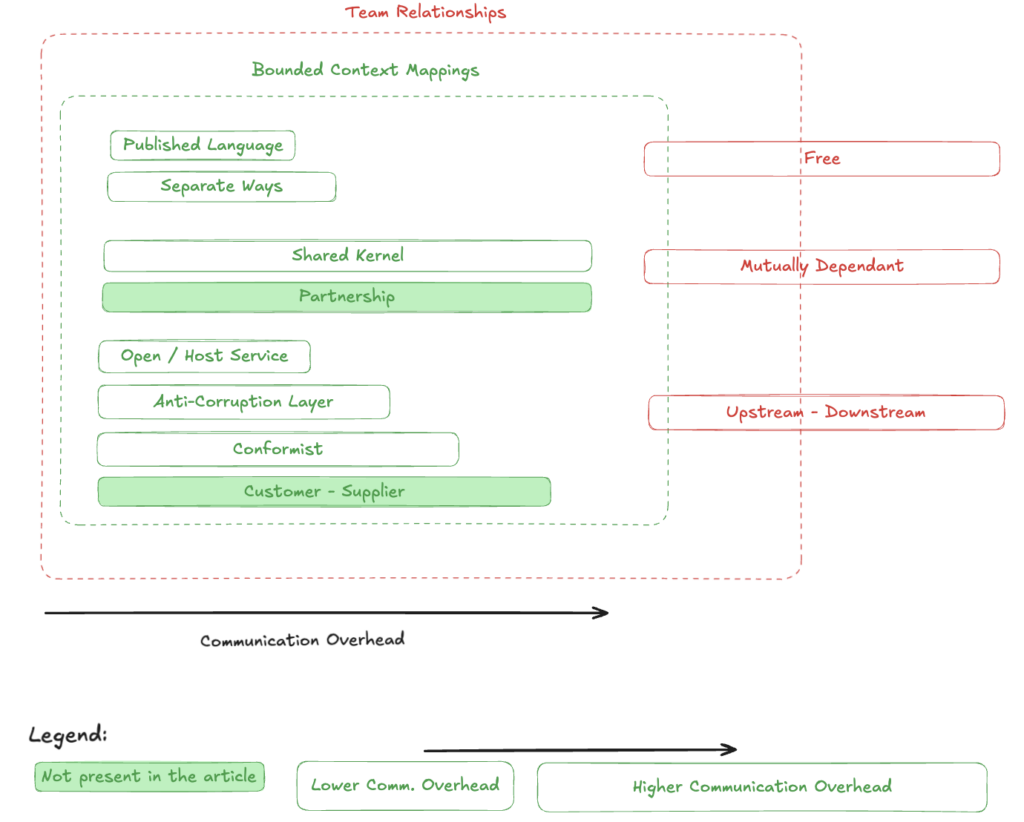

In the sources mentioned in the introduction, we can observe some ambiguity surrounding Bounded Contexts and a slight confusion between this concept and team relationship types. To provide more structure, I created my own diagram that separates the dependency of Bounded Contexts from team relationships. The concepts are very closely related, but I feel that this distinction hasn’t been clearly made in the books and materials I’ve read. This is simply my interpretation of the available literature. Let’s look at the image below:

As you can see, I didn’t cover two variations in the post:

- Customer-Supplier

- Partnership

I did this intentionally. In my understanding of Context Mapping, the Customer-Supplier and Partnership relationships refer more to communication between teams than to the technical conditions under which they connect. I believe they are self-explanatory from their names and there’s no need to go into more detail. I will address the issue of communication between teams in a separate article, where I will include the above-mentioned points and discuss the red blocks from the diagram in more detail.

Another element from the legend is the arrow, which describes the communication overhead between teams. This quite accurately reflects how much you need to coordinate with the team maintaining the neighboring business component and how many meetings/communications you will need to exchange with them. In some cases, this will be a significant criterion, for example, in situations where communication is not well-developed.

When we look at my visualization, we see that the green area is nested inside the red one. This also describes a certain hierarchy in the division of tasks. First, from a higher level, we look at communication between teams (or, if one team is responsible for multiple business capabilities, communication within that team), and only then do we go down to the level of mappings. That’s how I see it and that’s how I organize it in my mind.

Summary

I hope I have described the topic of Context Mapping in a reasonably clear way. From the perspective of strategic DDD, it is a very important element of system-level design. Many sources, presentations, and books describe context mapping in a very general way. I tried to break away from that and show examples of applications and systems that we encounter in our daily work or everyday life.

It’s important to remember, however, that at the enterprise level, Context Mapping is not just a technical exercise, but above all a powerful political tool. Every line on the map – whether Customer-Supplier or Conformist – reveals the actual power dynamics within the organization and the flow of decision-making. As architects, we must be aware that the choice of pattern often stems not from the elegance of the code, but from budgetary hierarchies or the willingness of teams to cooperate. Context mapping allows us to name these tensions explicitly, transforming architecture from a theoretical diagram into a real strategy for navigating the power structure within the company.

If you disagree with my arguments, notice any imperfections, or would like to discuss the topic further, please feel free to comment. We learn the most through exchanging ideas. Nothing is set in stone. Methodologies and concepts can change, and it’s important to keep up with market changes and adapt definitions to the world around us – never the other way around!

See you next time!